Georgia’s Cancer Registry Improves Access to High Quality Data to Assess Survival Rates and Adapt Public Health Strategies

In 2020, five years after introducing a population-based cancer registry in the country, public health experts at Georgia’s (Sakartvelo’s) National Center for Disease Control and Public Health were able to assess for the first time the five-year survival rates for different types of cancer. The achievement, which was hailed as an outstanding success by the IANPHI General Assembly, opened up the possibility to identify gaps in cancer care and adapt cancer control in the country.

Clinical oncologist Natia Jokhadze at one of Georgia's medical facilities caring for cancer patients, which are required to share information with NCDC's cancer registry (photo credit: NCDC)

Population-based cancer registries (PBCRs) are an important tool for the epidemiological surveillance of cancer. They allow the continuous, timely and systematic collection of data on cancer cases and mortality in order to evaluate their incidence, prevalence, trends and survival rates. Experts also use registries to monitor cancer screening and other preventive and management measures and to develop public health approaches against cancer.

In 2015, the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health (NCDC) implemented a population-based cancer registry in Georgia using the “CanReg-5” program, an open source tool developed by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (WHO/IARC) to input, store, check, and analyze population-based cancer registry data.

“Our objective was to have access to complete, accurate and timely data on cancer morbidity and mortality, that would enable us to estimate the main indicators of cancer care in the country and facilitate proper introduction and effective demonstration of cancer prevention and management measures,” said Dr. Nana Mebonia, head of NCDC’s Chronic Disease Division.

Prior to implementing the registry, NCDC collected cancer data through routine surveillance from about 200 medical facilities that provided services for oncological patients. However, family doctors caring for oncological patients were not required to participate in the data collection process.

“This approach provided incomplete data,” explained Dr. Mebonia. “In 2014, only 4,200 new cases were registered, while since 2015 and the implementation of the PBCR, more than 10,000 cancer new cases have been detected annually.”

When the registry was first introduced, notification of new cases was manual and paper-based, which resulted in incomplete case notifications and missing variables in registration forms. The staff managing the registry, whose number remains limited to this day, had to make additional requests to medical facilities.

In 2019, NCDC solved the issue by launching the Unified Electronic System for Cancer Data Collection to start collecting data electronically and combine information on cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment.

“Since cancer care is provided in multiple settings in Georgia, the complexity of data collection, management, and linkages was challenging,” said Dr. Mebonia.

The unified electronic system is used for the national cancer screening program for cervical, breast and colorectal cancers. Through the system, target populations are invited to regular screenings after screening a first time. This system stores detailed information about screening procedures, and results and calculates indicators used to assess screening performance, outcomes and participation of target populations. The unified system also supports better management of cancer patients – after obtaining patient consent, physicians have access to patients' electronic data.

The unified system is also connected to a birth-death module and the patient's life status is updated in real time, which enables the calculation of survival rates.

Although cancer survival depends on a patient’s access to effective medical care, their tumors (clinical, morphological and molecular), age, gender and comorbidity, survival rates are considered the main indicators for cancer management and care. They open the way to the detection of weak links in the chain of cancer care and to improved cancer control strategies.

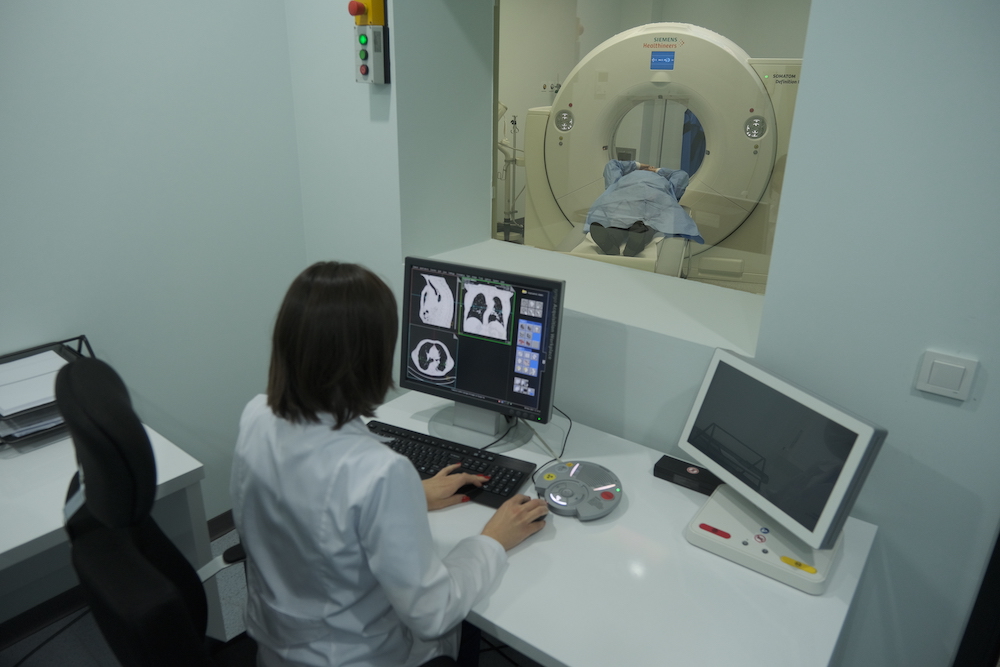

Radiologist Nino Batiashvili with a cancer patient (photo credit: NCDC)

NCDC’s efforts culminated in 2020, five years after launching its cancer registry, when the institute became able to calculate for the first time the five-year survival rates for different types of cancer.

The assessment of survival rates revealed that they are significantly lower in comparison to those in high-income countries. For instance, according to ranking by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the five-year survival rates of breast cancer are 76.5% in Georgia and 90.2% in the top-ranking country (United States). For colorectal cancer, the gap is wider with survival rates of 43.2% in Georgia and 80.1% in the top-ranking country (Australia).

In a next phase, Dr. Mebonia’s team identified the main predictive factors for low cancer survival rate, such as late detection and non-standardized approaches to cancer treatment. The team’s plans are now to influence those predictors – by promoting early detection of cancer and implementation of standard approaches to cancer treatment.

One of the other challenges awaiting Dr. Mebonia and her colleagues will be to move away from survival rates’ current calculation method. Called the direct method, it relies on the direct proportion of cancer patients who are alive after five years and does not use all the available data points.

NCDC plans to continue working closely with WHO/IARC and with the CONCORD program, a program for worldwide surveillance of trends in cancer survival led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, to compute survival rates through the use of advanced epidemiological methods, such as the one known as Kaplan-Mayor.

These efforts are part of a National Strategic Plan for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention and Management, which aims to improve quality control and multisectoral approaches and reach the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3.4 in relation to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) – reducing by one third premature mortality from noncommunicable diseases through prevention and treatment.

“Trends and determinants of NCDs should be continuously monitored and progress of their prevention and control evaluated,” said Dr. Mebonia. “This means Georgia needs to have access to high-quality national data in order to produce evidence-based policies and strategies. The information collected within the PBCR supports the assessment of cancer prevention and management.”

“In the future, our goal is to harmonize and integrate various data sources using big data, in order to get a complete picture of the burden of cancer and other noncommunicable diseases,” said Professor Amiran Gamkrelidze, director general of NCDC, who has been a fervent supporter of the PBCR project since its inception.

At the regional level, Georgia was among the first countries in the South Caucasus to introduce a PBCR and can now help its neighbors.

“We are ready to share our experience”, said Dr. Mebonia. “Georgian data, which provides fairly complete data on cancer indicators, can be used to assess regional morbidity and other indicators.”

If you are interested in learning more about this project, please reach out to Nana Mebonia, MD, PhD, head of the Division of Chronic Diseases and Injuries at Georgia’s National Center for Disease Control and Public Health (n.mebonia@ncdc.ge), and her colleagues Maia Kereselidze, MD, PhD, head of the Department of Medical Statistics (m.kereselidze@ncdc.ge), and Konstantine Kazanjan, head of the Noncommunicable Diseases and Healthcare Resources Utilization Statistics Division (k.kazanjan@ncdc.ge).