IANPHI’s Annual Meeting Discusses Health Inequality and Launches Rio Statement

Fifteen years after its creation at a conference at Brazil’s public health agency, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), the International Association of Public Health Institutes (IANPHI) returned to Fiocruz for its annual meeting, from December 1 to 3, 2021, with the central theme of inequities in health.

The three-day meeting culminated with the presentation of the Rio de Janeiro Statement on the Role of the National Institutes of Public Health in Facing Health Inequities. The document suggests the creation or strengthening of health equity observatories in associated institutions. It encourages national public health institutes (NPHIs) to gather data on social and economic inequities to better prioritize health services and implement public policies that reduce those inequities − pointed out as a major determinant of health and disease. Members were given the opportunity to comment on the declaration prior to its upcoming release.

Under the theme “Recovering from Pandemics: Building a Healthier and More Equitable World”, the annual meeting began with the general assembly, opened by Fiocruz President Dr. Nísia Trindade Lima, and under the impact of the emergence of a new variant of concern of SARS- CoV-2. Like the president of IANPHI, Prof. Duncan Selbie, Nísia highlighted the recognition of the role of NPHIs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and praised the association for connecting and helping to develop these organizations.

Recalling that the pandemic has made "social and health inequalities" clearer, Nísia stated that equity is not limited to the distribution of vaccines, but also supplies, such as gloves and masks that are lacking in many places. “In order to have a healthier world, we need a more equitable world,” she said. She further suggested that IANPHI deepen its relations with the World Health Organization and “raise its voice at all world health assemblies”.

The general assembly was followed by a series of sessions open to the public and held in partnership with Fiocruz’s Center for International Relations in Health (Cris/Fiocruz).

Dr. Nísia Trindade Lima, president of Fiocruz, gave the annual meeting’s keynote speech

Mobile Laboratories and Vaccination Buses

Several initiatives were shared at a session about health equity perspectives in NPHIs’ COVID-19 responses. Dr. Natalie Mayet, deputy director of South Africa's National Institute for Communicable Diseases, said her country had “weapons” to deal with the arrival of COVID-19, “but no ammunition”, in a reference to the lack of reagents for the SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic tests.

In South Africa, mobile laboratories providing COVID-19 antigen testing are covering the “points of entry” in the country. Georgia, for its part, has used “vaccination buses” and mobile groups to serve people with disabilities, said Dr. Natia Skhvitaridze, adviser to the director general at Georgia’s National Center for Disease Control and Public Health.

People living in vulnerable areas are more likely to test positive to COVID-19, noted Prof. Geneviève Chêne, chief executive of Santé publique France. “Mortality is also higher in the poorest areas,” she said. France invested in specific actions for the most vulnerable groups, such as immigrants.

Dr. Yujin Jeong, director of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, said her country was following the "strategy of 3Ts": testing, tracing, and treatment. To do so, it took advantage of the experience gained from the MERS outbreak in 2015. The country even tracked credit card transactions to follow the path of the virus and find people who were close contacts.

Health and Inequity

A session on health equity tools and strategies allowed participants to observe similar structural problems in different countries. Mexico, for example, saw the need to develop a program for indigenous people, who represent about 10% of its population. “Indigenous households are five times more likely to live in extreme poverty, their children are below average height, and mortality per thousand births is 14.4% in indigenous municipalities, against 10.2% in other areas,” said Dr. Juan Rivera, director of Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Salúd Publica. “We need to train health care students to be agents of change. Social justice must be a part of public health. We must apply the lens of equity”, he defended. Rivera suggested training indigenous healers to incorporate modern medicine practices, as was done with local midwives with good results.

Dr. Carlos Castañeda, director of National Health Observatory of Colombia’s Instituto Nacional de Salúd, said that the "gap is widening" for indigenous people, who are also major victims of the armed conflict the country has been experiencing for decades. Created ten years ago, the Observatory has been gathering data on social determinants, which show the vulnerability of indigenous populations.

Dr. Ir Por, lead of the Health System Research Center at Cambodia’s National Institute of Public Health, cited several equity-oriented actions which NPHIs can take to promote health equity, including developing equity networks of public health leaders and policy makers, and organizing workshops to deepen understanding of the importance of health equity. “Setting up an effective equity governance and monitoring system with local capacity is key to sustainably improving country health equity and achieving universal healthcare,” he said. “However, it is challenging and takes time to see results, as it requires a multi-sectoral approach which is much beyond the health sector responsibility.”

For Felix Rosenberg, a Fiocruz researcher and chair of the IANPHI Latin America Regional Network, everyone agrees with “the structural origin of inequalities and that, because they are structural, they tend to reproduce”. To face them, he advocates for intersectoral and local work.

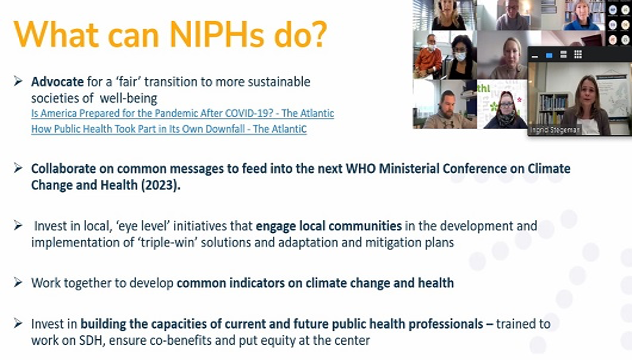

For three days, experts debated the role of public health institutes and the implications of climate change on global health

Climate and Health

On the third and last day of the meeting, a session was held to discuss integrating health equity in NPHIs’ climate and environmental action. Ingrid Stegeman, program manager at EuroHealthNet – a European network of 61 members in 26 countries – said that while no one is doubting the impact of climate change on health anymore, the problem resides in “moving from rhetoric to action”. She stated, “it is important to talk about a socially just transition. Reducing inequalities must be an increasing priority. This means adopting more political positions”.

Dr. Tatiana Marrufo, lead of the Program of Environment and Health at Mozambique’s Instituto Nacional de Saúde (INS), linked the prevalence of diseases such as cholera, diarrhea and malaria to extreme weather events, such as cyclones, floods and droughts. INS health observatory tries to predict health impacts in order to prepare responses, such as developing early warnings and investigating outbreaks.

Dr. Brecht Devleesschauwer, senior epidemiologist at Belgium’s Sciensano presented the ELLIS project, which aims to monitor and mitigate environmental health. It seeks to identify “stressors” that can increase the risk of disease and assess the impact of policies on inequities. To do so, it takes into account three factors: socio-economic deprivation, environmental exposure and health consequences.

Commenting on the recent United Nations Conferences on Climate Change, Luiz Augusto Galvão, senior researcher at Cris/Fiocruz, recalled that at the 2009 conference in Copenhagen, developed countries pledged US$ 30 billion in aid to the poorest countries, but that aid did not materialize. However, he said, the costs generated by the impacts of climate change, even for rich countries, were much higher. A positive note of this year’s COP26 in Glasgow, he mentioned, was the participation of civil society. Galvão defended compensation for losses and damages to developing countries, and a better North/South and South/South dialogue.

The IANPHI Annual Meeting ended with a few words from the new secretary general, Dr. Anne-Catherine Viso, for Dr. Jean-Claude Desenclos, who had been assuming the role since 2016. The next meeting will be hosted by the Public Health Agency of Sweden from November 30 to December 2, 2022, in Stockholm.